Repeat Spiral Plot

A tutorial by David Eccles about representing a repetitive DNA sequence in a visually-interesting form. This tutorial uses data from the nanopore WGS consortium and describes a process for generating an image similar to the following:

Accessory scripts

Process

- Download sequence data

- Troll for repetitive regions

- Identify repetitive subsequence

- Generate spiral plot

- Generate kmer dotplots

- Create montage using GIMP

Background

DNA is the recipe book of the living world. Every living thing has DNA in it; it codes for the things our bodies make, and tells the cells in our bodies what to do and where to go. When DNA is represented at an atomic level, we see that it is composed of four different nitrogenous bases: double and single carbon rings that are supported by a sugar/phosphate backbone.

Each of these bases can be represented symbolically as one of 4 letters: A, C, G and T. When combined into a string of sequential letters, we call it a DNA sequence. The process of converting from the physical thing of DNA into a model on a computer is called DNA sequencing.

[image: DNA sequence]

Sequencing DNA by Shape

Imagine there is a device that can scan across an image of DNA, like a photocopier, and work out how much black there is in each line of the image. What you end up with is a squashed down representation of the DNA, showing how much stuff there is at a particular place in the DNA.

If our line detector were sensitive enough, then we would be able to distinguish the four different bases just on this profile alone. A and G look similar, as do C and T. Similar, but a well-trained eye would be able to tell the difference.

[image: comparison of Sanger vs Nanopore sequencing]

Sequencing DNA by Nanopore

The Oxford Nanopore MinION contains a consumable flow cell, which has a commercial cost of about $1300. This flow cell has thousands of small sequencing pools, each which has a waterproof cover over the top. This cover is pierced by protein tunnels, which we call nanopores.

An electric current is hooked up to the flow cell, which encourages DNA to move through the nanopores. Similar to the previous “photocopier” image, the shape of the DNA changes along its length, and this changes the electrical resistance. The change in resistance is recorded by the sequencer and sent to a computer over a USB cable.

This sequencer is very portable: all it needs is some prepared DNA, and a little bit of electricity.

[image: nanopore diagram]

Nanoscopes and Wide-angle Lenses

Because the MinION sequences DNA by looking at it, it can show you things beyond what you could see from just knowing the A/C/G/T sequence.

Some features of prepared DNA can only be seen by looking at the electrical signal created by the MinION. It’s able to see chemical changes at a sub-base level, changes on the scale of a few nanometres. We have studied nanopore sequences at the electrical signal level for investigating whether there were epigenetic signals in unamplified mitochondrial DNA [1]. We have also used a signal-level analysis to distinguish between DNA sequences that were joined in-vitro during sample preparation and sequences that were joined in-silico by the base caller [2].

[image: chimeric reads]

And yet, at the other end of the scale, the MinION doesn’t limit the length of the DNA that is put into it. You can use this feature to look at repetitive structures, and maybe they’re not exactly repetitive after all, having more complex patterns, only visible when looking at the big picture.

When I use this sequencing device, I get glimpses like these about what might be missing in our knowledge of DNA, and I get really excited by that.

[image: nippo repeat region, showing spiral pattern]

Large-scale patterns in the human genome

We are used to DNA sequences being treated as essentially random noise that accidentally creates useful stuff from time to time. I’ve been discovering in many ways that this is not the case, and that there is an impressive amount of order in DNA, even in places where we currently believe that the DNA is functionless.

The Nanopore-WGS-consortium has recently published a paper on an assembly of the human genome derived from nanopore reads only.

In the paper, they stated that they had successfully assembled the Major Histocompatibility (MHC) locus, which is considered to be a very tricky region to sequence and analyse (from a genetic perspecive). I went fishing (using LAST-split) through their attempts at genome assembly, and found that one contiguous sequence of DNA from the ‘canu.35x.contigs.fasta’ assembly contained the entirety of the human MHC locus.

Imagine standing in the middle of a mostly featureless expanse of desert, every rock looks just as uninteresting and as randomly-placed as the others. Every straggly bush or tree seems haphazardly placed. But then you start walking, and taking pictures every kilometre or so; taking pictures of what appears to be a world of nothingness. A couple of weeks later, you’re revisiting the photos, and you notice that every third picture has a large rock in it that looks identical, and there’s a little patch of grass nearby. It’s a different part of the desert, you can tell by the timestamps on the pictures, but that same rock seems to keep appearing, again and again.

This is similar to what I’m seeing with DNA. On the surface, there doesn’t seem to be anything remarkably different between the sequence ACTCCAGCCTGGTGACAGAGTGAGA and the sequence ACTCCAGCTCACAGTCCTGTCGATG, yet the first one appears forty one times, and the second one only appears once in a DNA sequence 15,062,723 bases long.

I’ve been tinkering around with my own methods for trying to demonstrate DNA structure at a large-scale level, and thought that the HLA region would be an interesting experiment in this regard, leading to the above image. My current name for these things is “ripple” plots, because tandem-repetitive sequences in the DNA form images that remind me of the reflection of islands on water. Maybe there’s another name for them; I’d be very interested to know of it:

Ripple plot from tig18, showing two adjacent tandem repeats

In the above image, I’m looking at the structure of a DNA sequence with different lengths of kmers, where I decompose the sequence into overlapping subsequences of a given length (i.e. the k in kmer), and look at how frequently those subsequences appear elsewhere in the DNA sequence. Currently in this image I’m showing where the sequence itself is repeated (purple/red), as well as where it appears in reverse (yellow/green), and where it appears in reverse-complement (cyan/blue). The reverse and reverse-complement locations override the simple repeat locations, which is why there’s so much more blue than red in this image. However, that similarity can be seen below the diagonal in the more traditional self-vs-self dotoplot on the right hand side (representing the same data, just in a different way).

When I look at the ripple plot for the MHC locus, I see a lot of reverse-complementation throughout the region, and a few spikes where the reverse complementation is very close. I’ve only just started noticing these spikes, so I don’t really know what they mean (as is becoming more and more common for my recent work in looking at patterns in the DNA).

Just so that you don’t get the wrong idea about the abundance of these patterns, this “spiky” structure is not unique to the MHC locus. Here is a wider view where I’ve run the same display algorithm on the entire 15 Mb contig that included the MHC locus (highlighed in the image):

Ripple plot, tig01415017, kmer size = 27

And for completeness, here is a ripple plot for a completely random “DNA” sequence of the same length, with no repeated patterns seen anywhere:

Ripple plot, random DNA sequence, kmer size = 27

Source scripts used to generate these images (some assembly required):

- kmer dotplot script – includes “ripple” plot as an alternate display option

- dotplot annotator script – adds annotation to the plain ripple plot

Repeats in the Nippostrongylus brasiliensis genome

Our paper on the genome assembly of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis from nanopore reads is now out:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12915-017-0473-4

One of the most mentioned advantages of DNA sequencing on the nanopore is the long reads that it produces. Over the past year I’ve been exploring what that enables us to see that we couldn’t see before, and these repetitive regions are a good example of that.

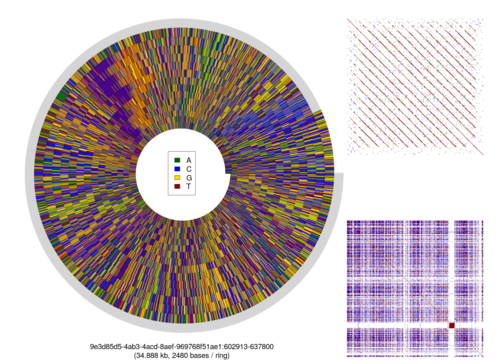

This image is showing a sub-sequence from one of the assembled pieces of the genome of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, a rodent parasite with a similar life cycle to human hookworm. The sequence spirals out from the centre, and I’ve created the spiral in such a way that every loop of the spiral has the same number of bases of DNA (the “bases per ring” value shown at the bottom of the image).

I usually put a key on these images (e.g. here), but have excluded it from this particular image. It uses the same colours for DNA sequence that are used in DNA sequencing electropherograms:

A: green; T: red; G: yellow; C: blue

We use those colours consistently to represent the different bases in our research paper.

I wrote my own R script to create these images from a FASTA sequence, then used gifsicle to combine them into an animated GIF. The sequence is from our assembled genome, available from here.

The lines radiating out from the centre of the image show bits of DNA that look the same in successive chunks of the sequence. The repetitive unit of approximately 3066 bases has no easily-detectable self-similarity: subsequences of that 3066-base repeat that are at least 13 bases long don’t appear anywhere else in the repeat unit. Here’s a 13-mer dotplot (created using a Perl script that I wrote) that attempts to demonstrate that, comparing the sequence to itself on the X and Y axes. Any repeated sequence appears as a red dot; any reverse-complemented sequence as a blue dot above the diagonal, and any reversed sequence as a green dot below the diagonal:

13-mer dotplot, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, tig7744

I’m still trying to rack my brains to work out why these regions exist, and what their function might be, but at least for now I can sit back and appreciate that they make beautiful pictures.

Discussion

=======

References

[1] https://f1000research.com/articles/6-56/v1

[2] https://f1000research.com/articles/6-631/v2